Metis Hotels and their Hoteliers

Metis was once the accommodation capital of the region. In 1929, when the Boulevard Perron opened and the Tour de la Gaspésie was inaugurated, there were more than 500 beds in more than two dozen commercial establishments in Metis. Its tourism economy had few equals in the region. Today, Metis has barely three dozen beds in just three commercial establishments. What happened to the fashionable seaside destination at the gateway to the Gaspé Peninsula?

Alexander Reford

Director, Reford Gardens

Metis has a tourism history different from other villages around the Gaspésie. It was among the first shoreline village to imagine tourism in its future. As early as 1849 it was being touted as a possible summer destination. When the descendants of the community’s founder, John Macnider, were seeking to lease or sell the Metis seigneurie in 1849, they advertised it as health destination where “a hotel could be built to welcome people wishing to live in the countryside if cholera makes its appearance in Quebec City next summer”1.

First tourist establishment

It was the saltwater cruises, “voyages aux eaux salées”, that brought the first tourists. The cruises from Quebec City were offered once every summer from 1856 onwards. Travellers got off the boat at Rimouski and made the trek by horse and buggy along the shore road to Metis. They stayed in the home of a Scotch farmer whose front door opened onto the St. Lawrence. The following summer, Robert Turriff advertised the first commercial tourism establishment: “the accommodation is good, and the table is furnished with the best the country will supply”2. The cost was $5 per week for single occupancy, $4 for double.

Turriff Hotel was among the first hotels in the region. Hotels had operated in Kamouraska from 1826 and in Cacouna from the 1840s. Amable St-Laurent’s Rimouski Hotel would open in July 1859. Not everyone was pleased, however. Because the steamboats arrived in Rimouski on a Sunday, it required those bringing them to Metis in horse and buggy to work on a Sunday. This was “an insuperable obstacle in the way of those who wish to keep that day holy”3, an anonymous author wrote in the pages of the Montreal Witness.

Turriff was a descendant of one of the original setters in Metis, among the handful of Scots that John Macnider had enticed to emigrate to settle his seigneurie. Born with an entrepreneurial spirit, Turriff owned a farm property which stretched back from the only sandy beach on the rocky shore, what is presently known as “Turriff’s Beach”. Within a year of its opening he was advertising having built a “new house” to accommodate visitors, “pleasantly situated on a point in Little Metis Bay, where the water is as salt as can be desired, and the convenience for bathing excellent”4. A discounted rate was offered to ministers of one or other churches, a cunning marketing policy designed to encourage the 19th century equivalent of influencers to endorse his establishment.

Turriff’s success brought competitors. In 1867, George Sylvain, advertised a house “suitable for summer bathing”5 in Sandy Bay. The following year, the Quebec Daily Mercury announced a new 20-room hotel opened by John Taylor, “lately from England”6. Turriff responded by opening Turriff Hall in 1871. A contented client shared his praise with the readers of the Montreal Daily Witness: “Mr Turriff, a well-to-do and most excellent man, has erected here a spacious hotel, well-arranged clean and orderly; meals plentiful and well-cooked, terms moderate. Persons whose tables are not very richly supplied must not expect a Delmonico kitchen [then the leading restaurant in New York City] at every country place, where they may alight, for four shillings a day, voracious children and nurses at half price – but remember they have milk, cream and eggs better that in town, and many other excellent things. We have finer fresh salmon than usually finds its place on the tables of sovereigns. In this climate porridge is in season all the year round, and the making of it is not likely to become a lost art in a Scotch settlement.”7

A popular destination

Metis began to attract attention. Journalist Ulric Barthe, who summered in nearby Baie-des-Sables, used the pages of La Gazette de Sorel, to promote Métis to “those who lured by rest, tranquillity, good air, sea bathing and gene-free [sans-gêne]”8. The resort thus aims to attract the “right people he meant the English-speaking Montrealers. Chief among them was William Dawson, principal of McGill University, who built a cottage in 1876. So many of McGill’s faculty followed Dawson that the main thoroughfare was sometimes referred to as “McGill College Avenue”.

The inauguration of service on the Intercolonial Railway (ICR) in July 1876 brought Metis closer to Montreal. Passengers for Metis would disembark at the Petit-Métis station, several miles above Metis, where they were met with a fleet of horse-drawn carriages to take them and their baggage down the hill to their hotels or cottages. The ICR added additional cars in the summer for the growing number of passengers destined for Metis. The service was so efficient that Montreal businessmen made Metis a weekend destination, leaving the city on an evening train so that they could join their families on Saturday morning. The train station was a veritable fête on Sunday evenings, with wives and children bidding farewell to industrious fathers returning to the city to be at work the following morning. This ritual persisted until the completion of the Canada and Gulf Terminal Railway, which added a station in Little Metis, where the same carnival-like atmosphere prevailed for decades.

The experience economy

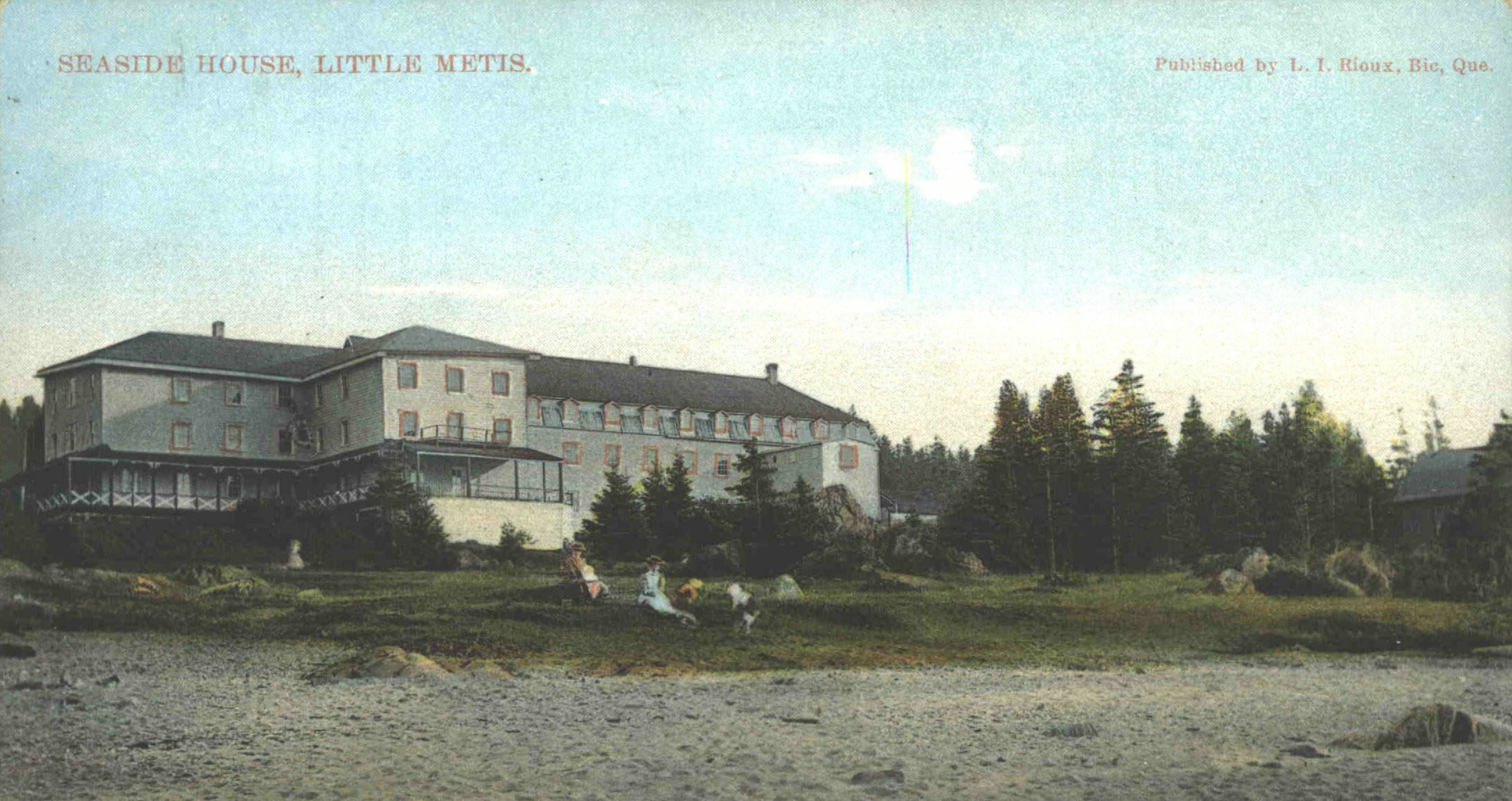

The growth in trade led to a construction boom. William Astle opened the Seaside House. Known locally as “Castle Astle”, it advertised itself as the largest of the hotels in Metis, with 150 rooms. The Astles had settled in Metis in the 1830s, their land not ideal for farming, but offering building sites for hotels and homes. Above the hotel, cottages were built to accommodate those eager for views of the St. Lawrence and access to the water’s edge. Rather than ruin the hotel business, the cottagers contributed to their growth. The Turriff and Astle families developed a thriving economy of rental properties. Cottages were built to suit the needs of the growing list of Montrealers who chose Metis over the shoreline communities of Cacouna and Murray Bay (today La Malbaie). The wealthiest built their own homes, but the majority were content take rooms in one of the hotels for as many as five or six weeks. Even those who stayed in cottages took their meals in the hotels, to avoid having to organize a cook or obtain provisions during the summer months.

The hoteliers created the experience economy. Excursions to the falls on the Metis River or to enjoy views from the rangs were organized by locals with horses and buggies. Trout fishing was offered on nearby lakes. Dining rooms, bowling allies and even a salt-water swimming pool became part of the complement of services on offer. Concerts were organized in the hotels, the benefits aiding the construction of churches to serve devout vacationers, a Methodist chapel in 1866 and the Little Metis Presbyterian Church in 1884.

The Turriff and Astle families formed the entrepreneurial class in Metis. The Blue, Campbell, Meikle and Macalister families opened businesses to provide groceries, gifts and boarding houses. The Astles opened the Seaside House in 1881, the Boule Rock Hotel in 1900 and the Metis Lodge in 1929. Descendants of John Macnider, who owned property in the centre of the village, joined the tourism industry, opening the Cascade Hotel in 1886. “Unrivalled sea view, First-Class board. Opposite telegraph and Post Office.”9 The town was the first in the region to have a volunteer fire department and install fire hydrants to connect houses to municipal water. Debate over who would benefit and who would pay unveiled tensions in the town. Taxpayers argued that the “hotel part of the village” should pay for services that other parts of the village did not enjoy.

The hotel boom

The heyday of the hotels in Metis was between 1929 and 1967. The Boulevard Perron, the Route 6, was completed in 1929. It opened the Tour de la Gaspésie to a new kind of tourist, travellers eager to explore North America by car. Group tours also began to offer week-long holidays to the region. A stay in Metis was often the starting and the end point for travellers on the Gaspé tour. The scenic highway spurred the construction of new hotels. Fred A. Astle opened the Metis Lodge, with 45 rooms, in 1929. Its special appeal included rooms with private baths, hot and cold water in all rooms and electric lights. Central heating was another draw. The Parkwood Hotel opened in 1931. The Boule Rock Hotel added suites with private baths to 75 of its 100 rooms and a 30’ x 70’ heated saltwater swimming pool, complete with a swimming instructor. Dancing and live music events for 200 were hosted in the dining room. The community had its own pharmacy that provided a range of products, including bottles of Vichy water, hair tonic and fly catchers.

The Great Depression was a challenge to the hotels and their survival. It also led to a murder in Metis when itinerant Albéric Taupier was hired to work at the Cascade Hotel as a groundskeeper. He killed hotel manager Kenneth Macnider Burke on the steps of the summer house of Mrs. Sidney Dawes. In spite of the bylaw prohibiting the sale of alcohol in Metis, the village became the home and warehouse for the notorious Prohibition bandit, Sunny White.10

Metis was among the first to form an association to promote a destination in the region, a “syndicat de promotion”, the origin of the present-day regional tourism associations. The Metis Beach Chamber of Commerce published several brochures, regrouping all of the major hoteliers and inventorying the many attractions of Metis. Hay-fever free was one of several taglines used to promote the destination.

The tourism economy prospered sufficiently that hotel owners had to look elsewhere for their staff. When the surrounding communities of Les Boules, Baie-des-Sables and Mont-Joli were not sufficient, entrepreneurs resorted to importing hotel staff from New Brunswick. Cooks were recruited in Montreal. Several of the hotels-built accommodation to house their workers during the summer months.

The surviving hotel registers of the Seaside House, Boule Rock, Cascade and Killiecrankie Inn illustrate how Metis attracted a clientele from near and far. Clients were primarily from Montreal, but many also came from Ottawa, Toronto and beyond. The majority were returning clients of the middle class, who took the same rooms year after year. The hotel registers confirm the degree to which the region, and Metis in particular, attracted visitors from outside Quebec, many more than the number visiting the region today.

The tourism bubble began to burst in the 1950s. The rising number of returning summer residents changed the dynamic of the village and its politics. Pressure built to remove the Route 6 and the traffic that traversed the village. With the highway bypass, automobiles skirted the village. Motels began to populate the tourism landscape. Some were opened in Ste-Flavie and Baie-Sables, but not in Metis. The hotel properties were built on postcard-size lots, with little or no room for parking. Hotel owners were confronted with the rising cost of insurance and the obligation to add emergency exits and exterior staircases. The danger of fire was real; several hotels burned to the ground, the Parkwood Hotel in 1940, Turriff Hall in 1941. The Metis Lodge succumbed to flames in 1958.

Today, there are few surviving vestiges of the once thriving hotel economy. The hotels are celebrated with historical plaques that tell the story of the entrepreneurial families who built them and the generations of visitors who made them their summer abode.

Notes

1. Le Journal de Québec, April 5 1849.

2-3. The Montreal Witness, July 15 1857.

4. The Montreal Witness, June 26 1858.

5-6. The Quebec Daily Mercury, July 14 1868.

7. The Montreal Witness, July 30 1879

8. « Les Excursionnistes », La Gazette de Sorel, June 28 1870.

9. The Montreal Daily Witness, May 15 1886.

10. See Alexander Reford, “La tempérance à Métis-sur-Mer”, Magazine Gaspésie, vol. 55, n° 3 (193), December 2018-March 2019, p. 23–25.

Photos (in order)

Turriff Hall Hotel was founded in 1871.

Collection Les Amis des Jardins de Métis

Dating back to 1881, the Seaside House Hotel was the first of three Astle establishments in the early 20th century.

Collection Les Amis des Jardins de Métis

Interior view of the Boule Rock Hotel, an Astle property, 1926.

Photo: Canadian National Railways

Bibliothèque et Archives Canada

Heated saltwater pool at the Boule Rock Hotel, 20th century.

Collection Les Amis des Jardins de Métis

Cover of the booklet designed by the Métis Beach Chamber of Commerce, 1950s.

Collection Les Amis des Jardins de Métis