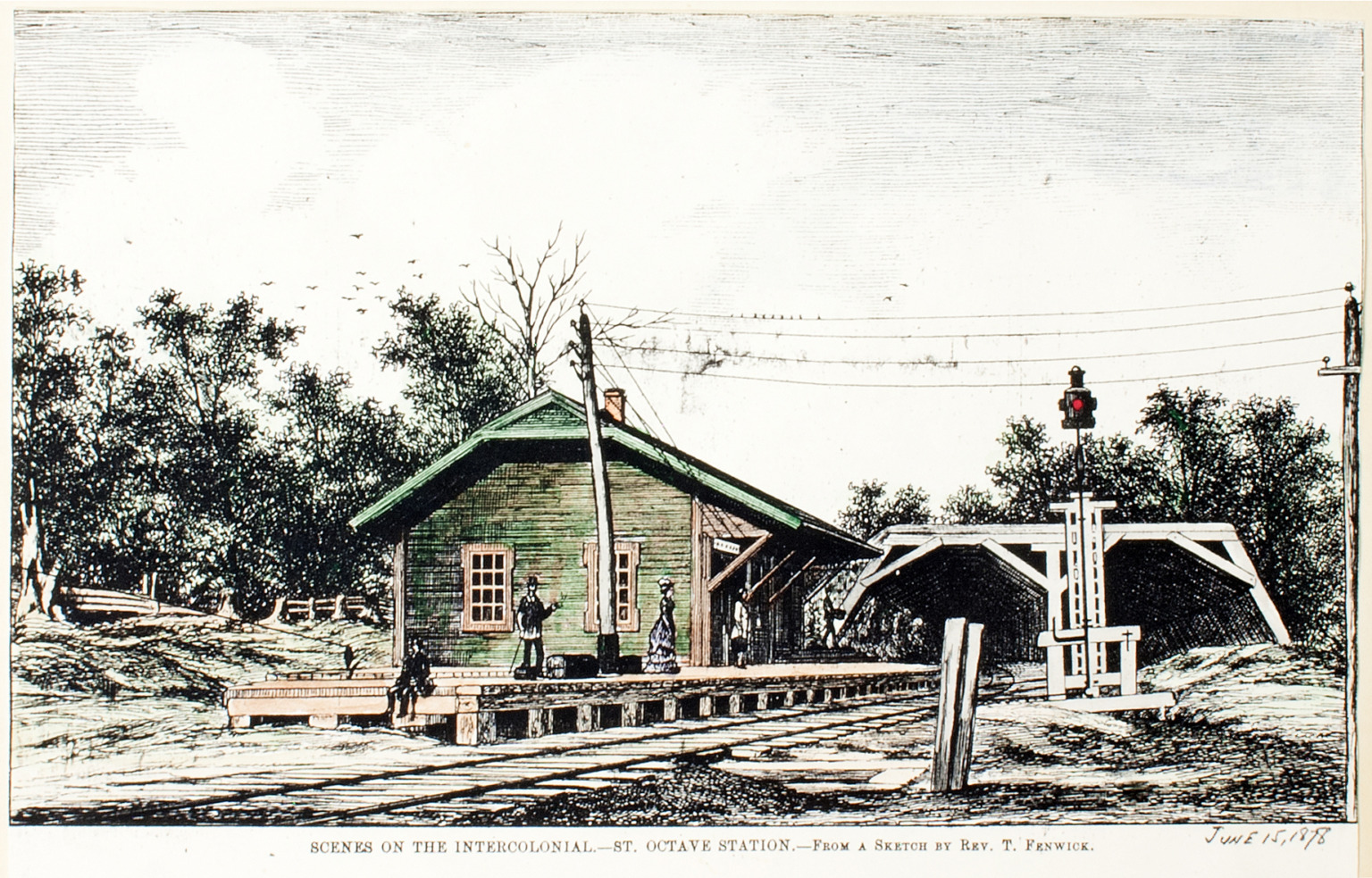

Last station

When the Intercolonial whistled through the Metis region it stopped in the wrong place. That at least was the conclusion of the villagers who found the St. Octave station poorly sited. It led to a cleavage in the municipality, fed a separatist movement that nearly split the village in two and finally resulted in the construction of a second station.

Alexander Reford

Historian and director, Reford Gardens, and St. Octave-de-Métis resident

When the Intercolonial Railway began service on July 1, 1876 trains stopped at the eastern end of the paroisse. From there the rail line takes a sweeping curve, a unique S configuration, engineered from the summit the Intercolonial reaches at its easternmost point along the St. Lawrence River to descend south into the valley of the Mitis River and on into the valley of the Matapedia. This station was incovenient for everyone. It was more than 4 miles distant from the church and village centre. Nobody lived there. It was in all probability sited during the construction of the railway itself, the natural point to assemble materials and men near to the blasting and excavation work engineered by Sandford Fleming to reroute the Tartigou River under the rail line.

The station’s location was also a political compromise. If it was incovenient to villagers, it was convenient to those travelling further east to Little Metis, Sandy Bay (Baie-des-Sables) and Matane. Not that convenient, mind you. When journalist Arthur Buies submitted his report on Matane County to the Mercier government in 1890, he quoted the pleas of the Sandy Bay curé who said that the farmers in his parish were condemned to poverty.

“The nearest railway station is St. Octave de Metis. Thirteen mies distant. How can cattle and sheep be sold with any profit when they have to walk so far? They tire on the way, are liable to accident from the temperature or otherwise, they arrive at the sation exhausted, run the risk of losing value and in any case a whole day must be lost in driving them there and other expenses incurred which take away all the profit, since the farmer is obliged to sell the cattle at the same price as the farmers of the adjacent parishes of Ste. Luce and Ste. Flavie, who have the Intercolonial at hand and sell their cattle on the spot of ship them by railway”.1

The plea finally led to the construction of the Canada and Gulf Terminal Railway, a branch line completed in 1910 from Mont-Joli to Matane (through Little Metis and Sandy Bay).

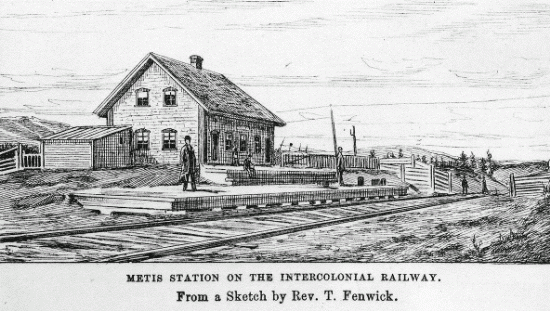

However inconvenient, the station would be a key infrastructure in the rapid development of Metis into a summer resort – making travel to and from the shoreline village, eight miles distant, much easier. Previously cottagers had to endure the perils of disembarking from ships onto a sailing skiff operated by seigneur John Ferguson that ventured out into the St. Lawrence at Lighthouse Point to collect passengers. William Dawson, Principal of McGill University, would begin construction of his shoreline cottage in 1876, leading a building boom of new homes for fellow Montrealers and hotels to service the growing tourist trade. The ride to and from the station became one of the attractions of the community and its rituals. Horse-driven buggeys took passengers to and from the station. This allowed the English-speaking visitors to enjoy the company of a local ‘habitant’ for the ride, however bumpy and dusty, excited by the spectacular vistas of the St. Lawrence as the lighthouse and comfortable homes came into view.

But soon after the inauguration of the Intercolonial service, pressure was exerted to build another station, this time in the village proper. Part of this was driven by a separatist movement of farmers who argued that the village and church should move to the train station rather than the other way round. Liberal member of parliament Jean-Baptiste Romuald Fiset (whose government had taken power in 1873) raised the issue in the House of Commons “asking that the station of St. Octave be placed in a more convenient situaution”.2 A new station was built, conveniently located where the railway traverses the Chemin Kempt, the historic road completed in the 1830s, a meeting of the transportation networks, old and new.

But it took another petition to change the name of the station – announced in the newspapers in June 1881. The original St. Octave Station would become the Little Metis Station and the Metis Flag Station would be called St. Octave (a “flag station” was a secondary station where the Intercolonial would make an unscheduled stop if a flag was put out by the station agent to signal a passenger to be picked up or let off).