The First Sound

My bed is snug. Getting a bit small for me as my fourth birthday approaches. I will get to move into a different room, with a larger bed. But for now, snug is good. Snug is warm and cozy. A circle of stuffed animals embraces me. Friend Hoppy Bear closest, at my right. Friend Squirrel at my feet. Blue-eyed, white pussycat at my head. Gray rabbit at my left. All the spaces inbetween filled with smaller furry friends, no less valued for being the smallest in the family. The same is true for me. I lay on my back, wriggle my toes and fingers to make sure all the creatures are resting in their places. All is quiet. Out of the darkness a deep sound booms. And continues to do so. The sound is regular. The same or very similar short spaces of silence between the booms. What can it be?

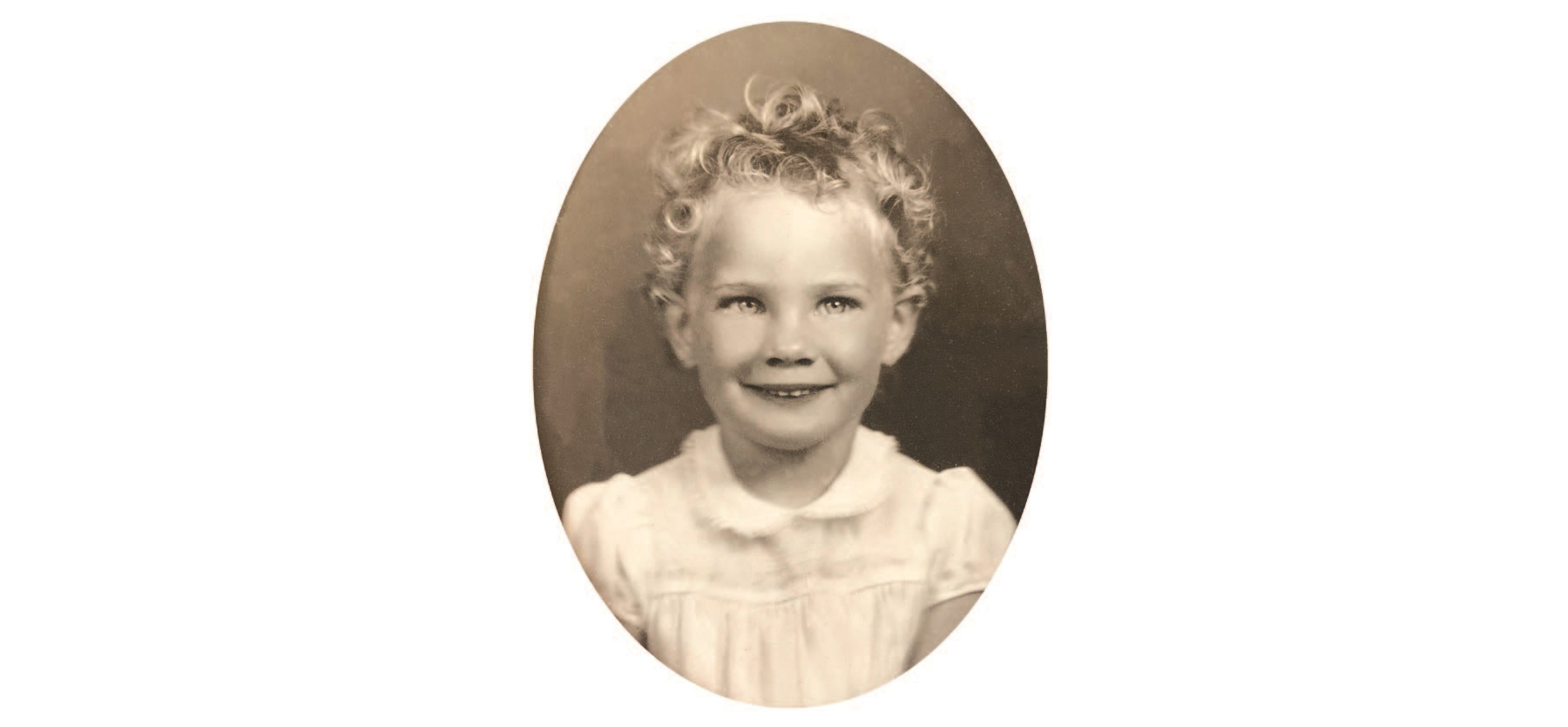

Cynthia Patterson

Resident of Barachois

This is not the moan of the foghorn. This is not the round, tumbling sounds of the bells at the cathedral. Not the spitting sound of a car driving too fast on the gravel street at the bottom of the gateroad. This is not the layered, rumbling sounds of ice pans breaking up on the river. And this is not the Spring of the year. This is certainly not the bossy shout of the neighbour’s rooster. And this is the dark of night, not the light of dawn.

What is this sound? Whatever it be, this is the first sound in my life that enters me, enters not only my ears, but my throat. I swallow this sound. It vibrates, reverberates inside me. I do not know those words, but I learn those feelings. The sound and its echoes arrive at a solid, dim place in the cave of my stomach. The sound is well in there, as am I in my bed. I go to sleep. The sound inside me goes to sleep. It sleeps for over 30 years.

We are boiling our kettle in the woods, one early spring afternoon after church. Mottled snow and green, flat field grass patch the clearing around us. The tin can’s hot coat hanger handle is lifted surely by an older man whose fingers tell stories of encounters with trees, with axes, with fish, with knives. Something in the positioning of the fingers whispers of paintbrushes. His cheeks are weather burnished. This is my grandfather, though unrelated. This is my uncle, though unrelated. This is my best friend, though a spread of years and experiences makes that seem unlikely. This is Tennyson Johnson.

Today’s boiling-our-kettle story is about another slice of Tennyson’s working life. When I think he has set out all the flavours of the times and places, all the tastes of life as a gandy dancer, a lumber jack, a fisherman, a guitar maker…when all those slices are set out on the plate of his life, there is always room for one more. Squeeze the others together a bit more. Make a little more room in your cup for more tea. Make a little more room on the log for the snow gnarled mitts to dry. Make a little more room on the plate of your memory for another slice of Tennyson Johnson’s life.

‘It must have around 1958 or ‘59. Thereabouts. I’d come out of the winter camps. Wanted to pick up some work before the fishing started. The river drives were over. The log booms were in circles near the mouth of the York River. A tugboat would nip and nudge them, like a dog rounding up sheep. Only these weren’t sheep. These were pulp wood logs. And these logs weren’t being corralled to another field or a barn. No. Those logs were headed for CIP lumber (Canadian International Paper). And I was waiting to catch them, haul them up and haul them in with my gaff on a long pole. Then they would go a little way, on a moving belt. They’d be carried up, then down. Like a roller coaster. And to come down, they slid on a long shute. And at the bottom of that shute they shot into the hull of the waiting boat. No more wooden boats here by then. They were steel. What a sound when one of those logs hit the steel of the floor or the wall of one of those boats! Especially when the boat was empty, or almost. That log hitting that steel didn’t make a thud. No, there was no thud. That sound rang deep, that sound traveled all the way to the bottoms of your boots. That sound traveled right across the river from Gaspe Harbour to Gaspe. Then that sound traveled all the way back again. It rolled right back from where it started. You could feel that sound in your heart, it was so deep.’

Tennyson! I spilled my tea onto the snow, staining it brown. That’s how excited I was! Tennyson, I was there!

What do you mean, you were there? You would have been only a child. And no children were there. The work was hard. You had to be quick, quick with your feet and your arms and hands. Quick with your eyes and inside your head, too. Otherwise, you’d be headed for an accident. And there was only one kind of accident in a place like that. A serious accident. There were big lights, way up high so we could work at night to get those boats loaded. No, you could not have been there. That was no place for children.’

But Tennyson, I was there. I really was. I remember the bright, strong lights. I grabbed the windowsill and I hoisted myself up in my bed. I remember the shute. I remember seeing the log booms in the daytime. I remember the tugboat. Most of all, I remember the sound. It’s still here, that deep sound. It’s still here in my belly. It’s in my chest and in my heart. That deep slam of wood on steel. That sound rolled right across the river to me. Then its echo rolled back across the river to you. I was there. You just couldn’t see me. And I couldn’t see you.

Tennyson, our friendship didn’t begin in 1984. It began around 1959.

C.I.P’s last shipment of pulpwood went out on the Birchton, 19 Nov., 1961. Although C.I.P. was a major employer for over three decades, with an imposing infrastructure in Gaspe Harbour, I have been unable to find a clear, detailed photograph of the loading operation.

Photos (in order)

Cynthia Patterson, 1959.

Collection Cynthia Patterson

Tennyson Johnson, untitled self-portrait, oil on wood, 29 x 24 cm, circa 2002.

Collection Jason Johnson

On the wharf, men take logs out of the water that were drained from the York River in Gaspé. On the right, we see a ship used to transport wood by Canadian International Paper (C.I.P.), 1951.

Musée de la Gaspésie. Fonds Lawrence C. Liebrecht. P187/1