Favorite ground for the study of native plants

Favorite ground for the study of native plants

The inventorying of the plants, birds and animals of the Gaspé was one of the earliest by-products of the Geological Survey. The creation of the newly formed united parliament of Upper and Lower Canada, the Survey was tasked with furnishing “a full and scientific description of the country’s rocks, soils, and minerals”. William Logan was appointed in 1842 to lead the Survey. The first region he explored was the Gaspé.

Alexander Reford

Historian and director, Reford Gardens

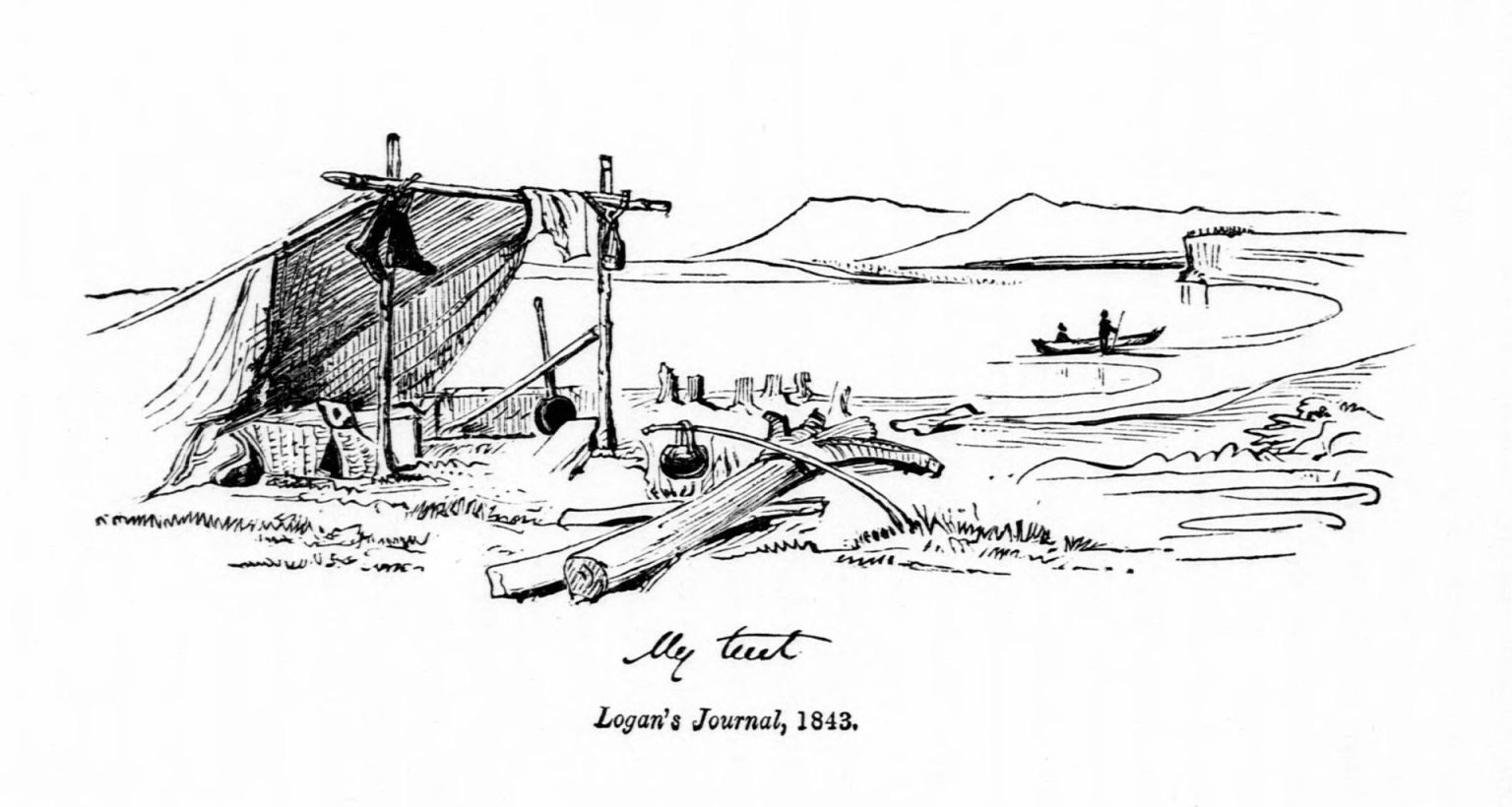

Logan’s diaries from his 1843 and 1844 expeditions reveal the endurance of this pioneering geologist as he clambered along the coastline, up cliffs and down steep slopes, aided by a young Mr. Stevens, from Bathurst, New Brunswick, and a First Nations guide, John Basque, who followed in a canoe. Local fishermen “…considered me, from my various gambols about the rocks, out of my mind”. Only at Cap Bon Ami did he find a home with a “capital little garden with the first flowers I have seen in part of the world in addition to abundance of cabbages and potatoes”. He brought the disappointing news to his government sponsor that the region had no coal but was rich in fossils.

Geology was a field of study in its infancy and its early practitioners were naturalists with a fascination for the natural world. They recorded the region’s flora and fauna out of personal and professional interest. Their findings were presented in government reports and before the Natural History Society of Montreal. Robert Bell‘s On the Natural History of the Lower St. Lawrence and the Distribution of Mollusca of Eastern Canada (1859) is the fruit of his expedition for the Geological Survey in 1857 and 1858. A bland inventory of mammals, fish, molluscs and flora, it offers a baseline list of the species of eastern Quebec observed before colonization had taken hold. Early travellers to the Gaspé occasionally remarked on the plants being cultivated. Thomas Pye’s 1866 Canadian Scenery District of Gaspé remarks on fertility of the soil and the success of farmers in the Gaspé basin in growing root crops and cereals (excepting wheat, although Abraham Coffin received an honourable mention at the Paris Exhibition in 1855 for his). “But….farming is unsystematic and much behind the age, all the energies of the people being devoted to the staple branch of industry – the fisheries”.

Logan’s observations of alpine flora in the Chic-Chocs led other geologists and botanists to follow in his steps. John Alpheus Allen, a student a Yale University, ventured north as part of a botanical party and inventoried 59 plants on Mont Albert and in the vicinity of Ste-Anne-des-Monts and Matane in 1881.[i] John Macoun of the Canadian Geological Survey collected a large number of Arctic flora on Mont-Albert for the National Herbarium of Canadian in 1882; he become semi-delirious while prospecting for plants because of black-fly bites.

In 1876, William Dawson brought a new dynamism to scientific observation in the region when he built a cottage in Little Metis. He would summer there every year until his death in 1899. Dawson was a geologist and his work as a paleobotanist had brought him acclaim and a mention in Darwin’s 1860 landmark publication the Origin of Species. Metis was where he penned many of his scientific articles (in several of which he argued against Darwin’s theory of natural selection) during his summer vacations. He observed the local shoreline on daily excursions with his rock hammer and collecting bag. His specimens were deposited at the Redpath Museum at McGill University where Dawson was Principal from 1855. Dawson’s interest in fossil plants meant that living flora was not of paramount importance. But he gifted his scientific curiosity to members of his family who shared his passion for the natural world. His son George Mercer Dawson would become a noted geologist in his own right. His daughter, Anna Lois, drew illustrations for Dawson’s articles.

The study of botany in academic institutions fostered plant expeditions around the world. Isolated locations like the Gaspé were of special interest to researchers in search of undisturbed populations of native plants. Harvard botanist M.L. Fernald made the Gaspé one of his areas of research from 1904 with a series of expeditions to identify new species. The unique alpine flora was central to his theory (now dismissed) that the 300 plants endemic to the Gulf of St. Lawrence region not found along the Appalachian Highlands was the result of the region having escaped the last phase of glaciation. Marie-Victorin relied on Fernald’s work for La Flore Laurentienne and to inform his own botanizing in the region.

Interest in plants extended beyond botanists. Summer residents were sometimes citizen scientists. The Rev. Robert Campbell, minister of the St. Gabriel Presbyterian Church in Montreal, wrote articles on the flora of Cap-à-l’Aigle. Dawson credits a “Miss Carey” for identifying species along the St. Lawrence. David Penhallow, professor of botany at McGill, inventoried the flora of Cacouna, while summering there. There are doubtless albums of watercolours and herbaria assembled by visitors to the region in the 19th and 20th century. Once found and inventoried, they will become important additions to the recording of the region’s flora by amateurs and professionals alike.

Photos (in order)

William Edmond Logan, My tent, 1843. Logan’s journals contain notes, but also sketches such as this one.

Illustration from: Bernard James Harrington, Life of Sir William E. Logan … first director of the Geological Survey of Canada, Montréal, Dawson Bros., 1883, p. 152.

Merritt Lyndon Fernald and his companions brave the difficulties of access during their mountain expeditions, 1923.

Courtesy of Archives of the Gray Herbarium, Harvard University

Brother Marie-Victorin during one of his stays in Gaspésie, 1930s.

Archives Université de Montréal. E01185FP009715