Let’s celebrate the 350th anniversary of the permanent settlement of Petite-Rivière in Barachois

Commencing on July 20, 2022, the village of Barachois will be hosting year-long celebrations to mark the 350th anniversary of the settlement of Petite-Rivière. This date bears historical meaning not only for this community but also for the Gaspé Peninsula.

Pascale Gagnon

Belle-Anse resident

For the Barachois and Area Development Committee

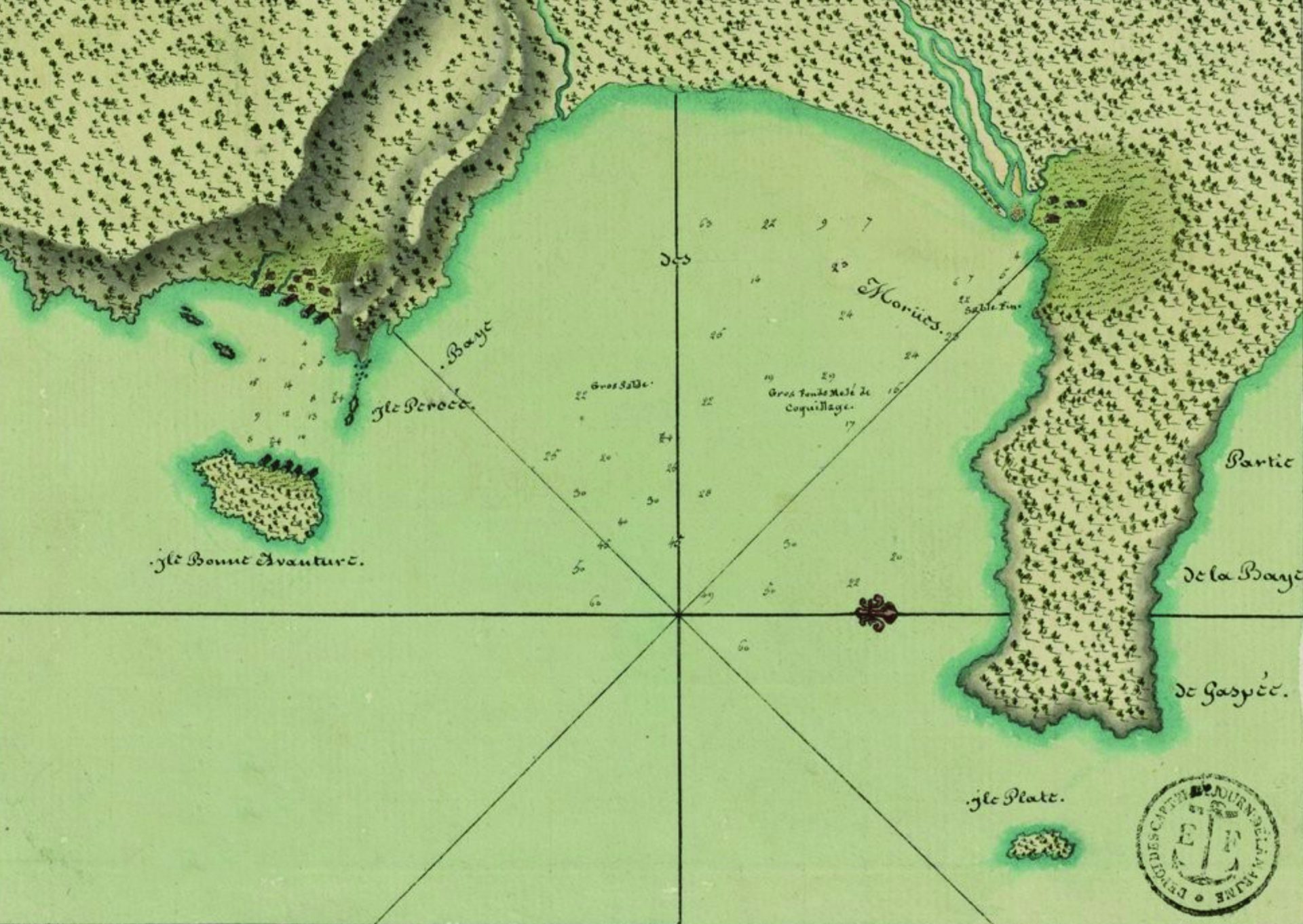

Indeed, it was on July 20 of 1672 that Pierre Denys de La Ronde, a merchant, and landowner from Québec, was granted a concession at the “rade de l’Isle Percée”. There, he built the Petite-Rivière Post where the village of Barachois is located today.1 To this day, this post is considered as the first permanent French settlement in the Gaspé Peninsula. Indigenous Peoples were the area’s only year-round residents prior to this settlement.

According to current map references, this concession spreads from L’Anse-à-Beaufils to Saint-Georges-de-Malbaie. However, it did not include Bonaventure Island, which was conceded two years later (in 1674) to Pierre Denys’ son, Simon Pierre de La Ronde.

The “rade de l’Isle Percée” bathes in the waters of the bay of Malbay (then called “baie des Molües”, “baie des Morües” or “baie de Forcemorue”) and is known as an exceptionally rich sea fishing area. The Mi’kmaq have been fishing there for a long time. The area has also attracted Basque fishermen and others, notably from La Rochelle, Bordeaux and Honfleur.

The small river within a lagoon (“petite rivière de barre”)

The concession granted to Pierre Denys de La Ronde forms part of a seigneury awarded to his uncle, Nicolas Denys, which spreads from Cap-des-Rosiers to the Strait of Canso in Nova Scotia. When visiting the “rade de l’Isle Percée”, Nicolas Denys was impressed with the potential of the bay’s natural resources, and its lagoon [translation]: “When leaving Bonne-Aventure and l’Isle Percée, we enter the baye des molües […] the coast leading to l’Isle Percée is made of mountains that are progressively lower and lower until they reach the deep end; there is a small river within a lagoon [“petite rivière de barre”] at the mouth of the bay, where rowboats only enter in good weather. The sea is quite far from the opening, and it is very shallow at low tide, with only a small channel for canoes; it is a large expanse of tidal flats and meadows that make for good hunting and fishing all kinds of shellfish; salmon is plentiful there; this place is quite pleasant, the land is bountiful and many types of trees can be found, some quite large, including beautiful firs; if the fishermen need trees for masting, they can find some there”.2

Although Nicolas Denys did not use the term “barachois” and instead described the area as a small river within a lagoon (“petite rivière de barre”), we know that the French used that term. They had adapted it from the Basque word “barratxoa”, which refers this type of natural formation and literally means a small bar (“petite barre”).3

Despite the economic interest presented by the “rade de l’Isle Percée”, Nicolas Denys did not fully deploy the efforts desired by the French authorities to develop its fishery in a structured fashion. At the time, about 400 to 600 fishermen fished in the area, but only on a seasonal basis. Pierre Denys de La Ronde committed to Intendant Jean Talon that he would establish a permanent and organized fishing settlement in the area.

An ideal location to live year-round

Immediately upon acquiring the concession in 1672, de La Ronde sets up two posts: one for seasonal fishing in a cove south of Percé and another in Petite-Rivière where a house could be built, the land cultivated, and one could live during the cold season. Four years later, in 1676, Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye and Charles Bazire joined de la Ronde’s enterprise and, together, the three associates founded the “Compagnie de l’Isle Percée.”

According to a map drawn by Le Moyne in 1687, the settlement in Petite-Rivière was located where the Saint-Pierre-de-Malbaie Church and des Coteaux Road are today (although this would need to be verified through archeological expertise). The site in Petite-Rivière was well protected due to the lagoon’s geographical configuration, and was therefore an ideal location for winter quarters.

In 1675, Chrestien LeClercq, a Recollet father who had just arrived in New France with Bishop de Laval, was given the mandate to accompany the fishermen of the Gaspé Peninsula and evangelize Indigenous peoples. On the 27th of October of that same year, LeClercq arrived in Petite-Rivière following a harrowing journey. There, he found a building large enough to welcome 15 people, 9 acres of cleared land, and 30 acres of deforested land, a landscaped and fenced garden, and a few farm animals. LeClercq lived 11 years in the Gaspé Peninsula after his time in Petite-Rivière, and left detailed observations about the daily life of the Mi’kmaq as well as the first French-Mi’kmaq dictionary.

“The ‘Lion d’or’ [Golden Lion], commanded by Captain Coûturier, was the first ship that I boarded to make my way as quickly as possible to ‘l’Isle Percé.’ We arrived there on the twenty-seventh day of October […] after much difficulty and hardship, we disembarked, thank goodness, and fortunately, at Mister Denys’ dwelling, at four o’clock in the afternoon, who was very well housed at the side of a basin commonly called ‘la Petite Riviere’ [small river], separated from the sea by a nice strip of land, making the amenities wonderful and this a most pleasant stay.”

Chrestien LeClercq, Nouvelle relation de la Gaspésie

A succession of trials

After a promising start, various challenges impaired the expansion of Pierre Denys de La Ronde’s company. One of his two associates, Charles Bazire, passed away barely a year after the company’s creation. The other, de La Chesnaye, could not invest the much-needed short-term funds. As for de La Ronde, being afflicted with blindness he went back to live in Québec. He delegated to his young and inexperienced son as well as his brother the care of the posts in Percé and Petite-Rivière. The colonists he employed complained of not obtaining the property titles for their lands and denounced this situation to higher levels. This undermined the authority of the de La Rondes and compelled them to defend their rights over the concession.

After 18 years of activity in Petite-Rivière, the final blow came in September 1690 when the settlement was burned down by New England privateers; one month after the Percé Post had experienced the same fate. Recollet father Emmanuel Jumeau recounted the episode to Chrestien LeClercq as follows [translation]: “But alas! My dear Father, I have reason to believe, and much fear that they are still experiencing the sinister effects of a second raid by these sworn enemies of our holy faith […] we had to promptly cut off our cables and sail away at the sight of seven enemy ships, that chased us in a strange manner, but that we were fortunately able to escape under the cover of night, during which we witnessed with great chagrin the burning of the houses in Petite-Riviere.”4

The families that had been living in the Percé and Petite-Rivière posts left the area to settle elsewhere. It seems Petite-Rivière remained unoccupied for the next 50 years or so, after which some activity resumed in the area. As of 1746, three families were living there: those of Aubin Lecouffle, (…) Thibeaudeau, and Guillaume Cochery.

That same year, Jean Chicoine, who was married to Marie Boudot and lived in Pointe-Saint-Pierre (and whose family moved to Petite-Rivière a few years later), raised the alert when a privateer ship docked in Petite-Rivière, after having roamed the waters of Gaspé Bay for two days. Such naval threats multiplied in the following years, most notably in 1758 when Wolfe and his men followed the Gaspé Peninsula coast and burned settlements along the shore. Despite this, nine people continued to live in the area according to a 1777 census.

Lot 27: the heart of present-day Barachois

In 1787, Nicolas Cox, the Gaspé Pensinsula’s first lieutenant-governor, had Gaspé’s Félix O’Hara build him a residence on lot number 27 in the Malbaie Township. The lot was granted to him in its entirety, and eventually became the heart of the present-day village of Barachois. For 10 years, the Cox residence was used as a government building that included a regional administrative centre, militia headquarters, and a court of justice, until Cox left the Malbaie Township for Chaleur Bay.

After Cox’s departure, lot 27 was occupied by Loyalists, who were eventually granted parcels of the land. The Loyalists joined the ranks of the few Canadians (a term then referring to the descendants of French colonists who were born on the territory extending from the Great Lakes to the Gaspé Peninsula) who were already settled there. They were joined over the years by Anglo-Norman, English, Irish, and Scottish families that established such deep roots in the area that their names are still found amongst Barachois’ inhabitants today.

The area known as Petite-Rivière also bore other names over the centuries: barécoi, barre à échouer, barachois de Malbaie, barachois de Mal-Bay, Saint-Pierre-de-Malbaie, and finally, Barachois. Livelihoods were made from its fishery, agriculture, logging industry, and tourism. Although the first three activities are no longer the economic engines they once were, the latter remains a strong attraction to the area. Barachois is a community deeply attached to its roots and proud of the exceptional beauty of its surroundings, which are as striking today as they were 350 years ago!

Notes

- In this article, the village of Barachois’ boundaries are deemed to be bounded on the west by Vauquelin Road, on the south by the barachois’ sand bar, on the north by des Coteaux Road, and on the east by du Moulin Street.

- Nicolas Denys, Description géographique et historique des costes de l’Amérique septentrionale, Avec l’histoire naturelle du Païs. Paris, Claude Barbin, 1672, p. 232-233.

- Genevière Joncas, « Barachois – Quand étymologie savante et étymologie populaire se confrontent… », Québec français, no 124, Hiver 2001-2002, p. 99-101.

- Chrestien LeClercq, Nouvelle relation de la Gaspésie qui contient Les Mœurs & la Religion des Sauvages Gafpefiens Porte-Croix, adorateurs du Soleil, & d’autres Peuples de l’Amerique Septentrionale, dite le Canada, Paris, Amable Auroy, 1691, p.14-15; citation en exergue p. 23-24.

Photos (in order)

- Cod fishing barges docking in the bay of Malbaie in Barachois in the 1940s.

Photo: Hedley V. Henderson

Musée de la Gaspésie. Robert Fortin Fund. P54/3b/1/2 - Le Moyne, Plan de la Rade de l’Isle-Percée et de la Baie des Morües avec ce qu’il y a de plus Remarquable fais en l’Année 1687, 1687.

Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France - Frederick William Blaiklock, excerpt from Plan of the township Mal Bay shewing the granted and unconceded lands in front range, 1858.

- Lot number 27, marked on the plan, is the heart of the current village of Barachois.

ANQ Québec, E21,SSS5,SS1,SSS1,PM,4B - The barachois of Malbaie and its sand bar, 2021.

Photo: Gérald McKenzie